A few months ago, in the course of writing about the phenomenal track record of the UMBC chess team, we briefly flicked at the notion that chess intelligence is a unique beast that doesn’t necessarily predict classroom (or life) success. The ability to imagine a game’s progress several moves ahead, as well as consider the implications of certain strategies before an opponent can even respond, is obviously a great skill, but one that doesn’t have nearly as many real-world applications as we’ve been led to believe.

A few months ago, in the course of writing about the phenomenal track record of the UMBC chess team, we briefly flicked at the notion that chess intelligence is a unique beast that doesn’t necessarily predict classroom (or life) success. The ability to imagine a game’s progress several moves ahead, as well as consider the implications of certain strategies before an opponent can even respond, is obviously a great skill, but one that doesn’t have nearly as many real-world applications as we’ve been led to believe.

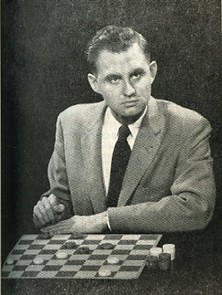

Ever since churning out that post, we’ve been thinking about a related topic: How does chess intelligence compare to checkers intelligence? Though the games take place on more-or-less identical boards, it’s widely acknowledged that checkers is the far inferior test of mental acuity. Yet some impressive minds have nonetheless made the game their life’s work, and none have been as venerated as Marion “Two Ton” Tinsley. In the world of checkers, Tinsley’s status as the greatest to ever play the game is unquestioned. And his legend is burnished by the fact that he never lost outright to Chinook, the computer program that eventually went on to solve checkers a dozen years after Tinsley’s passing. (Tinsley did lose to Chinook in 1994, the year before his death, but only by forfeit after he withdrew for medical reasons.)

We naturally wonder, then, what it is about Tinsley’s brain that made him the greatest checkers player that our species will likely ever produce. The man behind Chinook, Jonathan Schaeffer, attempted to answer that question in a chapter of his book One Jump Ahead. He cites various theories, including Tinsley’s stubbornness and focus. But Two Ton’s chief asset seems to have been his raw memory:

When Tinsley was young, he studied checkers eight hours a day, six days a week. In later years, after he became a strong player and his enthusiasm for competitive play waned, he only studied eight hours a week. The claim was that Tinsley could remember details from every one of those eight-hour sessions.

I first saw Tinsley analyzing one of his tournament games in 1990. I listened incredulously as he began to ramble on like this:

“I first played h6-g5 in the fourth round of the 1948 Cedar Point tourney against Leo Levitt. He responded with b4-a5 and went on to lose after g7-h6. After the game, I was analyzing the position with Walter Hellman at Morrison’s Cafeteria and we concluded that b4-c5 was the right move. Freyer played b4-c5 against me in the third round of the 1952 Canadian Open, and the g7-f6 attack failed to materialize. A few weeks after the event, while analyzing with Don Lafferty at his home in Kentucky, I discovered that b8-a7 instead of my f6-e5 follow-up would lead to a forced win, but I had to wait until the 1970 Southern States tourney before springing it on Fortman.”

Tinsley said he didn’t have a photographic memory. Whatever kind of memory he had, he seemed to supplement the checkers analysis with an incredible number of useless details. Maybe the useless details were the key to how he remembered things.

It sounds so easy when phrased like that. But keep in mind that checkers offers roughly 500 billion possible positions. It would seem that a human brain wouldn’t be able to conceive of the implications of each and every one of those arrangements. But Tinsley appears to have had a wee bit o’ cyborg in him.

He also did a killer job on a 1957 airing of To Tell the Truth.

scottstev // May 11, 2010 at 11:35 am

this fantastic article in the Atlantic covering Bobby Fischer’s pathetic end, makes the same point that chess facility != general intelligence.

Brendan I. Koerner // May 11, 2010 at 11:44 am

@scottstev: Wow, def. gonna read that. Fischer never ceases to baffle.

Given his preoccupation with conspiracies and his predilection for writing single-spaced pamphlets about his supposed enemies, my guess is that Fischer suffered from a form of paranoid schizophrenia. These are not the ramblings of a man with a realistic worldview:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vuSFZGTYdUo

Gramsci // May 11, 2010 at 12:08 pm

Bob Harris’s “Prisoner of Trebekistan” makes the point (entertainingly and raunchily) that memory depends on reinforcing associations– if you start with a graphic and easy association (you have to read Harris’s technique for learning the novels of E.M. Forster, but let’s just say “Howard’s End” anchors it), it will be easier to reinforce it. Tinsley’s memory might have been aided, as no doubt Fisher’s was, by his maniacal desire to figure out the game. He doesn’t just finish a game– he talks to Hellman, talks to Lafferty, tries to figure out all the ways that position could lead to a win. Those conversations help consolidate the memory further.

Brendan I. Koerner // May 11, 2010 at 1:27 pm

@Gramsci: Thanks for the comment. I still need to read that Harris books–if memory serves, this isn’t the first time it’s been mentioned on Microkhan.

Yeah, I think obsession is the real secret here. There was a study some years back (the particulars of which escape me) that sought to identify what separated the Olympic elite from athletes of a slightly lesser caliber. The study concluded that talent wasn’t the divider so much as a willingness to practice, practice, practice. Interestingly, the most elite athletes didn’t demonstrably enjoy practice any more than their lesser peers. They simply were able to endure the drudgery because of their obsessions with success.

I believe coaches call that “fire in the belly.”

Gramsci // May 11, 2010 at 4:51 pm

Or, as found in Agassi’s autobiography “Open”, it’s called “a father from hell.”

Jordan // May 11, 2010 at 6:38 pm

I think obsession really is the important part. It’s the desire to win over everything else. What always boggles my mind is how much work the runners up put in to never get the top spot.

Would These Men Juice? | Microkhan by Brendan I. Koerner // May 16, 2011 at 9:32 am

[…] at the ongoing World Draughts Championship in The Netherlands. (Previous checkers-related posting here.) In the course of keeping up on the tourney’s matches, I noticed something rather odd: the […]