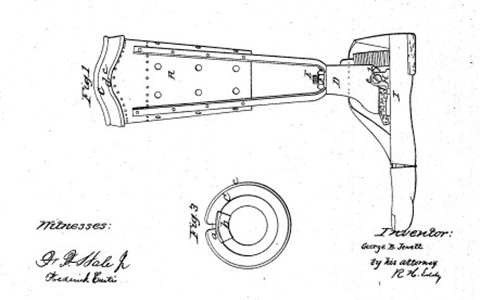

Amputations accounted for roughly three-quarters of all battlefield surgeries during the Civil War, which meant that artificial limbs were much in demand after the bitter conflict’s end. Captain Ahab-style wooden stumps were an easy fix, but they tended to severely curtail a man’s productivity. Fortunately for the shattered nation, then, a Massachusetts linguistics professor named George B. Jewett enjoyed dabbling in prosthetics whenever he had a spare moment. His great innovation, patented just months after the Confederacy’s surrender at Appomattox, was a novel artificial leg that featured something truly remarkable: a self-oiling mechanism, which allowed the limb to maintain maximum flexibility despite inclement weather or owner neglect.

Jewett’s company, headquartered at the corner of Park and Tremont Streets in Boston, did a brisk business with the Union’s former enemies, as states below the Mason-Dixon line launched public programs to supply veterans with artificial legs. North Carolina led the way, though some recipients of the state’s largesse were careful not to rely too heavily on their Jewetts:

It became the first of the former Confederate states to offer artificial limbs to amputees. The General Assembly passed a resolution in February 1866 to provide artificial legs, or an equivalent sum of money (seventy dollars) to amputees who could not use them. Because artificial arms were not considered very functional, the state did not offer them, or equivalent money (fifty dollars), until 1867. While North Carolina operated its artificial limbs program, 1,550 Confederate veterans contacted the government for help.

One Tar Heel veteran, Robert Alexander Hanna, had enlisted in the Confederate army on July 1, 1861. Two years later at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Hanna suffered wounds in the head and the left leg, just above the ankle joint. He suffered for about a month, with the wound oozing pus, before an amputation was done. After the war, Hanna received a wooden Jewett’s Patent Leg from the state in January 1867. According to family members, he saved that leg for special occasions, having made other artificial limbs to help him do his farmwork. (One homemade leg had a bull’s hoof for a foot.) The special care helped the Jewett’s Patent Leg last. When Hanna died in 1917 at about eighty-five years old, he had had the artificial leg for fifty years.

I’d be curious to know whether Jewett’s invention had any influence on the celebrated Jaipur foot, another prosthetic innovation that has done wonders for economic development.

ADW // Jul 26, 2010 at 3:38 pm

I’m sure it did influence the development of the Jaipur foot. How often do we lose sight of how important each step of the process is when we become preoccupied with the end result? (sloppy sentence, but it’s Monday)

“We had a lot of opposition from formally trained doctors. In a way, someone who’s not so educated is much more free.”

The guy thought he could make a leg and made a leg. Perfect.

Anyhow, this was refreshing break from the heaviness of the news lately. Much fun from thinking about a lot of the ridiculousness of the world today. I had a similar response to the article at Longform.org on Russian dogs riding the subway in Moscow – “Why should they go by foot if they can move around by public transport?” I often wondered that too.

Brendan I. Koerner // Jul 26, 2010 at 3:46 pm

@ADW: Glad to see you over here–enjoyed your comments over at TNC’s last week.

Central and Eastern Europeans are wonderfully chill about having dogs in public places. On my first trip to the Czech Republic, I remember being pleasantly stunned by the sheer number of mutts in bars–even in the wee hours of the morning, or in establishments where food was served. Not the sort of thing that American health inspectors will ever tolerate.

ADW // Jul 26, 2010 at 4:07 pm

Mexico, as well. I lived in Mexico City the year between undergrad and grad school, and one of the first things I noticed is how much the attitude of the street dogs reflected the attitude of the citizens. They were very chill, just kind of doing their thing, going about their day. One of the family’s that I lived with regularly put food and water out for a family of dogs in the neighborhood. The dogs would eat the food but snubbed their noses at the clear water in the bowl. You’d see the mom lead her pups down the way to the curb to drink the gray/black water flowing into the drains. Perhaps the clean water lacked a certain flavor – I don’t know, but it was hysterical to watch.

It was also interesting to see how the citizens responded to the dogs. I remember a dead dog lying on the well-manicured lawn of the school I attended – El Colegio de Mexico – for quite some time while the gardener would drive the lawn mower around the dog. I suppose they expected that at some point the dog would be sucked into the earth.

Anyway, dogs are fun to watch. When I lived in New York, I always paid attention to the happy care-free pooches of the UWS versus the harder edged canines of Harlem. It’s hard out there for a ghetto pooch.

goldnick // Jul 26, 2010 at 5:00 pm

Fascinating stuff! I guess I always wondered when the technology switched from “Ahab-style” peg legs to more realistic and foot like prosthetics.

Also, did Union states not offer prosthetics to their wounded, or did they just use a different supplier?

Brendan I. Koerner // Jul 26, 2010 at 6:10 pm

@goldnick: Good question! I believe that the Union may have started a federally funded program during the conflict itself, rather than leaving things up to the states. But I’ll have to double-check.

Jewett was by no means the only prosthetics company in the game, despite his valuable patent on the self-oiling artificial leg. There were other successful enterprises, notably J.E. Hanger (now the Hanger Orthopedic Group). Competition for government contracts was probably intense. And it probably led to a lot more innovation in the field. too.

Jordan // Jul 26, 2010 at 11:24 pm

Government procurement contracts definitely work a lot better if they hand out the qualities they’re looking for and let people figure out how to fulfill them. That can get everyone in trouble though. The military often seems to have nearly impossible standards to meet, which when coupled with the various forms of graft in the system leads to absurdly expensive stuff. On the other hand, that’s also moved technology forward in some important ways, so it’s not all a waste.