After a gestation period that lasted nearly a year, my latest Wired story is finally out. It’s a tough one to summarize, but the tale centers on a Cuban-Latvian engineer who figured out a way to replicate the slot machines manufactured by International Game Technology (IGT), the S&P 500 company that has long dominated the slots industry. I don’t want to reveal too much about the plot beyond that, lest I ruin the reading experience for y’all. Please, check it our for yourself and, should it give you some small dose of pleasure, help spread the good word.

After a gestation period that lasted nearly a year, my latest Wired story is finally out. It’s a tough one to summarize, but the tale centers on a Cuban-Latvian engineer who figured out a way to replicate the slot machines manufactured by International Game Technology (IGT), the S&P 500 company that has long dominated the slots industry. I don’t want to reveal too much about the plot beyond that, lest I ruin the reading experience for y’all. Please, check it our for yourself and, should it give you some small dose of pleasure, help spread the good word.

But I’m happy to offer some extras throughout the week, as is my wont when major projects drop. The detail I’ve been dying to share with y’all is the one about the invention that has come to define modern slot machines, a patent that vastly improved casino revenues by convincing players that their eyes could allow them to accurately assess a machine’s odds. As I explain in the story:

Slots didn’t truly become America’s favorite casino pastime until a Norwegian mathematician named Inge Telnaes came up with the most brilliant gambling innovation since the point spread.

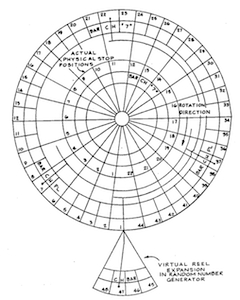

The problem with slot machines, as Telnaes saw it, was that their jackpots were limited by the number of reels they could use. Since players expected each reel to have no more than 10 to 15 symbols, a machine needed many reels to make the odds long enough to justify a huge payout when all the cherries or bells settled into a row. But the more reels a machine had, the more players were reminded of the fact that their quest for riches would likely end in futility; no one wanted to try their luck on a machine with dozens of reels (or, alternatively, hundreds and hundreds of symbols on enormous reels).

Telnaes’ solution to this conundrum was US Patent Number 4,448,419, awarded in 1984. His invention called for slot machine results to be determined not by the spinning of reels but by a random-number generator. The reels on such a machine would display only a visual representation of the generator’s results, lining up when a winning number spit forth or (far more frequently) settling into a losing mishmash of symbols. The patent made possible the development of slot machines that could offer extremely long odds—and thus enticingly massive jackpots—while still appearing to have just a few tumblers.

The fact that random number generators power all modern slots suggests that any money spent on tip books is money completely wasted. Yet there is no shortage of media that promises to teach paying customers how to beat those dastardly one-armed bandits. In the end, of course, playing slots requires no more skill than playing Candy Land. Less, even: you have to count the spaces in Candy Land.

Please, read on, and I’ll have more story extras as the week progresses.

scottstev // Jul 19, 2011 at 12:47 pm

I always loved strategy books for games such as craps and roulette. My favorite is The Martingale System, which “works” so long as you have an infinite amount of money at your disposal. Much like Steve Martin’s plan for turning 1 million into 2 million dollars (“first get a million dollars”).

scottstev // Jul 19, 2011 at 1:02 pm

BTW I love the “copy of a copy” effect in the illustrations. Kudos to the art director and illustrator on that one.

Brendan I. Koerner // Jul 19, 2011 at 4:52 pm

@scottstev: Just noticed that “copy of a copy” effect–didn’t come through so vividly in the PDF proofs that I get prior to publication, and I haven’t really looked at the story since it went live. (Rarely, if ever, read my own stuff.) Agreed that it’s awesome–very tough to story to illustrate, since it’s all about circuit boards, so they the art maestros did a great job.

Wish I could’ve gotten a good picture of Cabrera himself, but I wasn’t permitted to take any recording devices or cameras into the ICE detention facility. It crossed my mind to try and sneak something in, but I ultimately decided that it wasn’t worth the risk–would’ve lost my key interview if the gamble didn’t pay off.

Brian Moore // Jul 20, 2011 at 11:51 am

I’m really enjoying the article. Tell Wired that you helped them with at least 1 additional [old-fashioned print] subscription! 🙂

Captured Shadow // Jul 20, 2011 at 11:52 am

Interesting article! I wonder how tempted he was to put in a little backdoor payout scheme into the software so he could go on a winning spree at the casino of his choice………….

Brendan I. Koerner // Jul 21, 2011 at 10:58 am

@Brian Moore: Many thanks! I’ll def. let the bosses know that I helped secure them an extra set of eyeballs (as well as his $15 or so).

@Captured Shadow: A lot of people have asked that question. In fact, when I describe the story to folks, they usually assume that the entire scheme was done to score jackpots. But I honestly believe the thought never crossed Cabrera’s mind. He has no personal interest in gambling–he was just fascinated by the technology.

Richard (Dick) Paul Killian, Slot Repair Shop Manager June 1969 to June, 198419 // Mar 17, 2014 at 2:04 am

Automatic accounting for slot machines research was developed by Bally Manufacturing at its subsidiary offices on Timber Way in Reno, by the summer of 1975. Inge Telanae, Dick Raven led a crew of electronic engineers demonstrated their version to me in August of that year. Visionary concepts were suggested and grudgingly incorporated over the next 6 years on site at the Las Vegas Hilton. I wanted the slot industry to have accuracy in accounting first! .By 1981 0.04% was the accuracy level accomplished predicting the hard count daily. This evolved into “Ticket-In & Ticket-Out” with loyalty marketing programs etc. More than $4,500,000.00 was invested in the project.

Richard (Dick) Paul Killian, Slot Repair Shop Manager June 1969 to June, 198419 // Mar 17, 2014 at 2:18 am

While the Liberty Bell had 10 reel stops on each reel (10 X 10 X 10 = 1000), Jennings, Mills, Bally, Pace slots used 20 reel stops. (20 X 20 X 20 =8000). In the late 1960s Bally had added 22 stops. (22 X 22 X 22 = 10,648). Jennings had been using 25 stops (25X 25 X 25 = 15,625) beginning before I worked for Lincoln Fitzgerald at the Nevada Lodge, Crystal Bay, Nevada circa 1959. There were a few 36 stop Games of Nevada slots during those times (36 X 36 X 36 = 46,658).