I had to do a double-take this morning when I saw that The New York Times had a (digital) front-page feature on the Freedmen controversy. The question of whether Black Indians deserve tribal membership is something I wrote about six years ago, in a mammoth Wired piece that pondered the role of genetic analysis in this debate. One of the historic details I included in that story is worth noting in light of the Cherokee Nation’s claims that the Freedmen aren’t really Indian. It concerns the Dawes Roll, the 1906 census of Oklahoma Indians that the tribes claim is the only acceptable way to document Native American heritage:

The Dawes Roll was the brainchild of a patrician Massachusetts senator, Henry Laurens Dawes, who wanted to “civilize” Indian territory by ending communal land ownership and allotting 160-acre plots to individual members of each tribe. At first, the tribes resisted the white man’s efforts to destroy a centuries-old way of life. One Creek official compared the Dawes Commission, which oversaw the roll’s creation, to the plague of locusts the Egyptians faced in the Bible. But the tribes relented, if only to avoid a conflict with the US government.

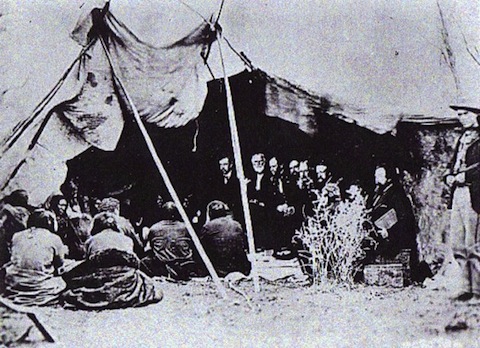

The task of enrolling the Indians was assigned to white clerks dispatched from Washington. They set up vast tent villages in Oklahoma towns and sent word through tribal officials that anyone interested in claiming their land had to register. Once the news spread, the tents were deluged with applicants, including scores of Caucasians claiming to have a sliver of Indian blood. More surprising for the clerks were the thousands of African-Americans who showed up. The 1890 census counted 18,636 people “of Negro descent in the Five Tribes.” With no ability to speak any Native American language, the clerks often relied on the eyeball test. Those who fit the stereotype – ruddy skin, straight hair, high cheekbones – were placed on the “blood roll.” The roll noted each person’s “blood quantum,” the fraction of their parentage that was ostensibly Native American. That number was sometimes based on documentation, but often, given the lack of accurate records and the language barrier, it was nothing more than crude guesswork.

Those with obvious African roots were sent to a different set of tents. There, they were added to the Freedmen Roll, which had no listing of blood quantum. Contemporary Freedmen believe the segregation was part of a government conspiracy to steal Indian land. Freedmen, unlike their peers on the blood roll, were permitted to sell their land without clearing the transaction through the Indian Bureau. That made the poorly educated Freedmen easy marks for white settlers migrating from the Deep South. Stories abound of Freedmen, unable to read the contracts they were signing, selling their 160-acre plots for as little as $15.

The haphazard nature of the Dawes clerks’ methodology means that there are Freedmen who, at a genetic level, can probably claim to possess more Native American DNA than enrolled tribal members—a fact that gives lie to the Cherokee argument that their stance is meant to preserve a coherent Indian racial identity.

The attendant issues of memory, sovereignty, and meaning are far too complex to unpack in this limited space. But as long as the Cherokees and other tribes insist on clinging to a biological myth perpetuated by early 20th-century bureaucrats, it’s going to be hard to take their other concerns seriously. Besides, hasn’t history repeatedly shown that nations only prosper when they expand their notion of citizenship beyond mere ethnic affiliation?

Jordan // Sep 16, 2011 at 1:58 pm

That reminds me of the story about Walter Plecker in “A Voyage Long and Strange” by Tony Horwitz. Plecker believed that there were very few “true” Native Americans in Virginia and used the one-drop rule to reclassify many of them as black. This had led to a lot of similar problems as blacks who believe that they have Native ancestors are excluded from the tribes because the tribes fear that allowing them in will lead to all members of the tribe losing their status.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_Ashby_Plecker