While in Pittsburgh last week, I had a chance to catch up with an old friend who’s now an archaeology professor. He just returned to the Lower 48 after four years in Alaska, where he spent much of his time digging up the artifacts left behind by ancient inhabitants of the Aleutian Islands. On our third pint of the evening, the conversation turned to whale hunting, which I’ve always understood to be an essential part of Native Alaskan culture. My pal confirmed that this was the case, but added a new twist with which I was previously unfamiliar: the role of shamanism in the slaying of cetaceans.

While in Pittsburgh last week, I had a chance to catch up with an old friend who’s now an archaeology professor. He just returned to the Lower 48 after four years in Alaska, where he spent much of his time digging up the artifacts left behind by ancient inhabitants of the Aleutian Islands. On our third pint of the evening, the conversation turned to whale hunting, which I’ve always understood to be an essential part of Native Alaskan culture. My pal confirmed that this was the case, but added a new twist with which I was previously unfamiliar: the role of shamanism in the slaying of cetaceans.

For the Alutiiq people, whale hunting was not a communal activity. It was, instead, an activity pursued by loners reputed to have mystical powers, whose mastery of this arcane and lethal art condemned them to lifetimes of isolation. A Russian missionary of the 1880s provided a description of how, exactly, these shamans managed to take down whales despite their utter lack of metallurgical technology:

The pursuit of whales was encumbered witli many observances and superstitions. The spear-heads used in hunting the whale were greased with human fat, or portions of human bodies were tied to them, obtained from corpses found in burial caves, or portions of a widow’s garments, or some poisoned roots or weed. All such objects had their own special properties and influence, and the whalers always kept them in their bidarkas. The hunter who launched a spear provided with such a charm upon a whale at once blew upon his hands, and having sent one spear and struck the whale, he would not throw again, but would proceed at once to his home, separate himself from his people in a specially-constructed hovel, where he remained three days without food or drink, and without touching or looking upon a female. During this time of seclusion he snorted occasionally in imitation of the wounded and dying whale, in order to prevent the whale struck by him from leaving the coast. On the fourth day he emerged from his seclusion and bathed in the sea, shrieking in a hoarse voice and beating the water with his hands. Then, taking with him a companion, he proceeded to the shore where he presumed the whale had lodged, and if the animal was dead he commenced at once to cut out the place where the death-wound had been inflicted. If the whale was not dead the hunter once more returned to his home and continued washing himself until the whale died.

I am impressed not only by the bravery required to confront a whale armed with nothing more than a poison-tipped sliver of shale, but by the mental fortitude it took to live this hermit-like lifestyle. I have to wonder why anyone would volunteer for this service, knowing that, at best, they would die alone in a frozen cave, and then have their body cannibalized by the next whale shaman. My friend suggests that this life was not a choice, but rather something that was thrust upon young men deemed eccentric by their villages—perhaps due to what we today would call mental illness.

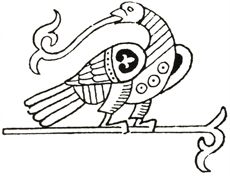

More on Alutiiq whale shamanism here, including the petroglyphs that the hunters created in their ample spare time.

scottstev // Dec 20, 2011 at 10:15 am

If your friend doesn’t get a letter like this, then he’s doing it wrong.

Brendan I. Koerner // Dec 20, 2011 at 10:21 am

@scottstev: Haha, classic. Love the innuendo regarding the relationship with Short Round, one of the most irritating sidekicks in cinematic history.