One of Microkhan’s top Alaskan correspondents recently alerted me to the existence of Project Facade, one of the eeriest and coolest art projects to be found on The Tubes. The endeavor is tough to describe in a pithy sentence or two, so please bear with me as I try: Project Facade is one artist’s attempt to create visual interpretations of the plastic surgery techniques pioneered by Sir Harold Gillies during World War I. Many of the resulting items are phantasmagoric uniforms that are decorated with before and after pictures of soldiers who underwent Gillies’ knife, as well as stitched surgical notes taken from Gillies’ files.

The project got me thinking about one of the few upsides of war: the development of advanced medical technology and techniques, which always outlast the quarrels that cause violent conflict. That was especially true during World War I, as detailed in this engrossing read from the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. There are tons of great nuggets strewn throughout, such as the fact that the mortality rate from femur fractures was an astounding 80 percent before doctors figured out how to minimize the occurrence of sepsis. But anyone who’s kept track of the current battle over vaccinations must take special note of the following anecdote:

As late as the last decade of the 19th century typhoid was still causing 5000 deaths annually, and in the Crimean War it had caused greater mortality than the war itself. Colonel Sir Almroth Wright began trials using vaccines made from killed typhoid bacilli on himself and the military surgeons at the Royal Victoria Hospital at Netley…Wholesale inoculation of British troops was attempted in the South African War but due to bitter opposition from influential persons less than 4% of the soldiers received the vaccine. As a result of this blunder the Army had some 58 000 cases of typhoid and about 9000 deaths.

During the whole of the Great War there were 7423 British cases, with 266 deaths, in an average strength of 1 200 000…In January 1916 records showed a British death rate from typhoid 31 times higher among the unprotected. In June 1916 the ratio had increased to 50 to one, a fact brought home to the public by a popular medical journalist of the time. Goodwin made the point in 1919 that inoculation was still voluntary in the British Army and that in 1914 the efforts made to persuade the men to have it were met by “the production of the page of a certain daily journal which strongly advised against inoculation.” He goes on to state: “I think it says something for the persuasive powers of our eloquence and for the intelligence of the British soldier that we were able to overcome this most pernicious advice, and that 98% of our Army were inoculated against the disease.”

I’m curious if anyone knows of other major medical advances that were developed during wartime, in order to keep as many soldiers on the battlefield as possible. (Or, at the very least, to keep those soldiers confident that relatively minor wounds wouldn’t permanently disable them.) One that immediately pops to mind, which I touched on briefly in , is how doctors at the 20th General Hospital in Ledo, India, conducted pioneering heart-bypass experimentation on stray dogs during their rare free moments.

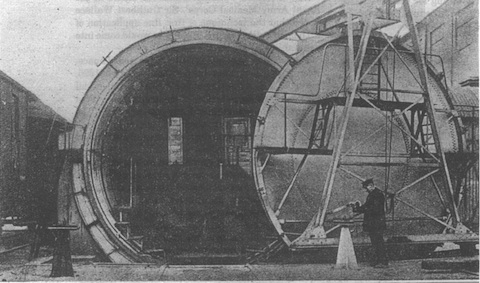

Oh, and the image at the top of this post? It’s a German train-car disinfection machine. Much more effective than a generous hand washing, apparently.

Jordan // Oct 4, 2010 at 11:22 am

While it wasn’t discovered during the war, penicillin mass production was certainly stimulated by WWII.

The precursors to blood banks were developed during WWI.

Brendan I. Koerner // Oct 4, 2010 at 12:02 pm

@Jordan: I’m fascinated by both of those innovations.

On the penicillin front, it’s interesting how the Allies never quite mastered the art of manufacture and distribution to the far-flung corners of the globe. I’m currently working on a major project about a man who died in ’45 for want to simple antibiotics. I’d like to learn more about the organizational challenges that prevented penicillin from becoming universally available during the war itself.

As for blood banks, I’d like to do a future Microkhan post about the segregation of blood during World War II–something that I discussed in great depth in an early draft of Now the Hell Will Start, though the finished product contains only a footnote. Maybe later this week or early next…

Tony Comstock // Oct 4, 2010 at 4:46 pm

How about a twist? IIRC, back in the 90s the army was sending surgeons to South Central LA so they could get first hand experience treating gunshot wounds.

I reckon that hasn’t been necessary this decade.

Jordan // Oct 4, 2010 at 9:08 pm

Early forms of penicillin were kind of tricky. The pharmacokinetic properties are really lousy. Something like 80% of it gets excreted in a couple of hours, so it’s hard to keep enough inside the system to do any good. Apparently before semi-synthetics were available, doctors would often collect the urine of patients being treated with penicillin so they could reextract the unmetabolized penicillin. So yeah, just having enough on hand to do any good would have been fairly tricky at that point.