In exploring the nuttiness of the Symbionese Liberation Army as part of my book research, I came across this bygone Congressional document: a transcript of a 1976 hearing entitled “Threats to the Peaceful Observance of the Bicentennial.” The artifact’s real gold is not to be found in the back-and-forth between various Congressmen and witnesses, but rather in the appendices that catalog pamphlets from the protest movements of the day. This was a difficult period for the organizers of popular discontent, given that both Vietnam and Watergate had vanished as rallying points. The focus of their ire was instead something that should sound quite familiar to contemporary ears: the concentration of wealth in very few hands, a situation made possible by the overly cozy relationship between industry and politics. It’s instructive to check out the typical rhetoric these protestors employed, to note the similarities and differences with today’s Occupy movement:

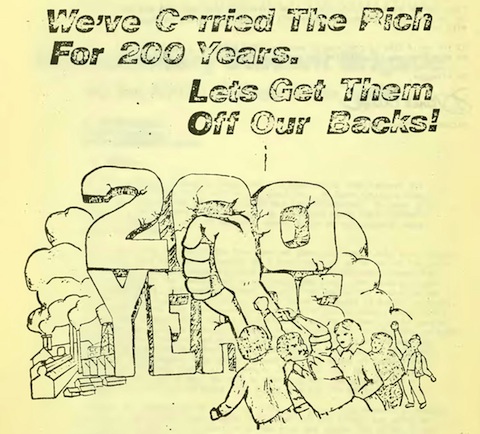

We’ve been robbed of the fruits of our labor by that class of parasites that runs the government and all of society for their profits and luxury. And even the gains of our struggle, like our unions, they try to turn against us. What is this “common interest” between us and the owners? For 200 years our hard work and all it has produced has carried a small handful of bosses and enabled them to live in riches and luxury, while this constant drive for profit has held back our labor from being used to meet the needs of the millions. Nothing has ever been handed to us by them, everything we ever got we had to fight for, even in so-called good times…

Now in this 200th year the bosses and politicians are hoping they can cool off our anger and struggle against these conditions by trying to play off our genuine feelings of pride in our hard work and its accomplishments. This is what’s really the point of their Bicentennial blitz and the calls for us to come to a July 4th festival in Philadelphia to celebrate life under this system which enables them to live like kings.

The bicentennial protestors’ core sentiment has a lot in common with what drives the Occupiers—the feeling that the wealthy few are totally oblivious to the increasingly difficult lives of the many. (See here for a bit of street-theater that would be right at home in Zucotti Park.) But take heed of the explicit notes of class conflict that echo the rhetoric employed by the totalitarian regimes of the ’70s—check out, for example, that line about labor being “held back” from providing for the masses. That sort of lingo obviously seems archaic in a post-Berlin Wall world, which is why—at least at its most successful—the Occupy movement has replaced broad ideology with heartfelt personal narrative. The movement’s participants may not convey a politically coherent message, but to criticize that aspect of the protests is to miss the point entirely; the participants are the message.

The other major difference between 1976 and today: the protestors back then were apparently really terrible artists.

eve // Jan 12, 2012 at 2:10 am

My husband just informed me that my latest investment tip bears a striking resemblance to this post.

http://wishwewerethere.wordpress.com/2012/01/12/occu-buy-buy-buy/

And this comment bears a striking resemblance to something approximating highbrow spam, I realize.

Brendan I. Koerner // Jan 12, 2012 at 3:08 pm

@eve: I find that heartening. I have a longstanding fascination with radical groups of that era, which in part spurred me to tackle this next book (in which groups such as the Weathermen and the Brotherhood of Eternal Love make important cameos). Good to know that others share my interest.